At University I took a course on the films of Ingmar Bergman. During the semester we would gather on Wednesday nights and watch two of the master’s films. One week we started with Through a Glass Darkly, and walked out for the break, a bit shell-shocked. When we went back in, prof Marc Gervais told us “ok, you’ve had your fun, you’ve had your laughs. Now we get dark,” and proceeded to show us Winter Light, perhaps the Bergman that I love the most. I was astonished by the film, but gutted at the end of that double bill.

The first time I saw Alexander Nanau’s film Collective was at the Helsinki DocPoint festival in February of 2020. It was also a double bill. I had watched Feras Fayyad’s The Cave just before that. So I flashed back a little to my Bergman moment.

The story of Collective is triggered by a horrific fire at a Bucharest nightclub in 2015, that killed 64 people and injured more than twice that number. The cause of the fire revealed mishandling and negligence. The responsibility for allowing the event is even murkier, and everyone passes the buck.

But the story of the film starts afterwards, when the survivors started dying. They shouldn’t have. They should have recovered. The public was told everything was under control. It wasn’t.

Following a team of journalists from the Bucharest Sports Gazette newspaper, Collective is at once a fascinating investigative documentary, and a horrific expose negligence and corruption at the highest levels of power. Hard to watch, and gripping at the same time.

I met Alexander (we think) three years ago, when we were both in Riga as tutors at the Baltic Sea Forum Documentary event. We broke bread while wearing bibs to save our clothes from seafood sprays, talked about Romania (and the piece of it that is in Montreal), and life in Sweden.

He made time to chat with me last week. Our talk, naturally, rolled out over Zoom, from Alexander’s living room to mine, as he and his team campaign in the run up to the Academy Awards, as his film Collective is competing for the best documentary Oscar. Even with a string of awards behind the film, the challenges of the campaign are present.

AN. It’s at a completely different level. We’re lucky that we have a top notch team between Magnolia and Participant, and our publicists. Everybody has their own field of expertise, and the countries are divided between different publicists. It’s a great experience to learn how you can bring even a documentary worldwide to an audience. But it’s work. Even the number of outlets and journalists who write about the film and keep writing on a daily basis… Just insane. The fabulous thing is that people react so well to the film. We already had that before the pandemic, and important journalists saying ‘this is really relevant for the whole world,’ from the very first reviews of the film.

P. How did you find out about the Sports Gazette story?

AN. We were looking for characters, basically mapping all people that were involved, from politicians to doctors to hospital managers to the families of the victims, trying to see who might be the right characters to follow and try and understand this whole situation: the manipulative power that did that to these people, and lied about the treatment, killed them basically. And while we were doing this, 10 days or two weeks after the fire, there was only one journalistic team who really investigated what the authorities were saying. The rest of the press was just propagating what they (the authorities) were saying. They exposed that the fire department had lied that they didn’t even know the club existed. They even authorized it (the show). And then they went further to investigate the hospitals, and found out there was one newly opened burn unit two months earlier. It was super modern, and as they said up to standards for treating burn patients. But it was then closed down. It had only been opened for the TV cameras.

At that point we thought we would never get access to the authorities, so if we want to understand power and how it works and how it violates peoples’ lives and rights, maybe the best way would be to follow investigative journalists.

P. And they didn’t have any problem with the access?

AN. They denied at first. They were polite but very straight in saying “that’s not possible, you can’t film in a newsroom, it has to be a protected space. We have to protect information and potential whistle blowers’’ and so forth. I said please take another look at my films. Think about it.

He called me one day and said “listen we are onto something, and I can’t tell you what it is. But we could try to film a bit around it to see if it works out.” And once we started I don’t think it took too many days for us to get the right speed, and carefully get the right stuff. They said that if professionals were interested in making a film about how the press works, maybe that could be a chance to communicate with a certain generation that the press has lost. That actually get their information from social media.

P. did you know that you were starting to make a film about the health care system from the beginning? Or did that reveal itself over time?

AN. We just started from the idea that we had chosen the right characters to follow. It was clear that it was linked to the health care system, that lied to the victims and their families, and mistreated the patients. But it was not clear from the beginning that it would go so deep into the health care system, with such incredible links of corruption to the political sphere. And then finding out that the pharmaceutical company had been diluting the disinfectants for ten years, and that the secret service knew and informed the politicians, and the health care system. I mean nobody could ever have imagined the magnitude of it… no. Or that one day we would get access to the ministry of health.

P. I couldn’t quite wrap my head around the fact that you were in there following them. Given how much you’d already shown how opaque they were. And Vlad of course comes across as a pretty sympathetic minister compared to his predecessor. I was asking myself: what am I really watching here? Is this a publicity stunt by the government to give the impression of a more transparent system? Or was it genuine?

AN. It was genuine to him. And to the team around him that allowed it. The previous health minister, even though it was an interim government, was trying to cover for the pharma company. No one from politics or with links to the system would ever allow him or herself to give access, because anyone inside the system giving access or being transparent is seen as a traitor. It would mean the end of his or her career. We were lucky that they appointed this complete outsider.

Everywhere we went with the film viewers were shocked by the level of access. Everybody felt like the film gave them insight into something they might not be allowed to see. Even in countries like Switzerland, or the Netherlands, people feel like they don’t have the right to know what their own institutions are doing. That they don’t really have the right to know about the decisions being made inside. You ask yourself ‘in Sweden, why have they decided that?’ How will we ever know the truth about why they handled the pandemic like that? People feel like once politicians are in power they are entitled to being secretive about their intentions. Our attitude is wrong. And they use it. And I think that anybody in any political or other system in the world we live in now has the feeling that they own that system, and they have the right to be secretive about their intentions. Which was not the case with our protagonist.

P. Right. And on that level, the previous minister and the scandal that came out, how much everything was sort of dirty inside of there… Vlad’s arrival felt like a reaction to that.

AN. I think it was basically their way of trying to find a solution which would absorb the anger of society. Just half a year before the government was brought down by the anger in the streets, and now people were back in the streets. So they thought “ok, let’s appoint this 33 year old guy. People will trust him. He’s an activist for patients. How much harm can he do in half a year?”

I only recently saw Toto and His Sisters, Alexander’s previous and much lauded feature doc. On reflection I noted that both films have a driving narrative that could easily be in a scripted fiction film, one a thriller, the other a taut melodrama. Part of that is probably because of my own affection for observational doc, but the structures themselves are lean. Toto is a much more personal, character driven story, but there are few moments of meandering. In both films, there are bold shifts in point of view. Particularly in Collective. In a sense it shouldn’t work.

P. There’s a passing of the torch around the middle of the film, where the film gets handed over to Vlad the minister, and Tolontan (the editor) goes into the background. Were you thinking about that shift during production? Or did that come more together in post production?

AN. I definitely thought about it. I already had an image in my mind of what kind of film it might be, and how I would try to keep the tension for the viewer as we witnessed it. But why do you pass the torch? Why would an audience still be interested if this is a film about journalism? Do you start from scratch? Do you start by putting context together? You don’t have that time. You’ll lose the audience in the middle of the film.

In Toto, it took a while to learn when and why to change storylines in a film. Because on paper it might look logical when to switch characters and stories, but it’s different once you’re watching the film, feeling its rhythm.

In the editing room there were dozens of attempts on how to change storylines. How much information do you have to give away about Vlad? Do you maybe use the journalist watching TV presenting this new minister, who he is, his backstory and everything? And then I understood that the most important thing is to get the viewer interested, by making him curious about who this guy is, by doubting him. And then it is a story that is glued together by life attitudes, that you always compare to your own. You know; “what would I do if that were me?” But it took a while to understand that.

P. I’ve struggled with some of the same questions in films I have edited, about shifting points of view. Trying to keep it reasonably seamless. It’s so difficult, because you have an arc going one way and then suddenly… well why is this person here?

AN. It’s really about triggering the viewer’s need to compare themself to the courage of some people, to life attitudes, and once you have him asking “why do these people have the courage to do this,” or “why would this woman blow the whistle when she basically participated in it (the malpractice)”, and “would I do those things, then later decide that they’re not good or right?…” I think that if you keep not only the heart of people but also their minds connected with the characters then they all become one character, which is your viewer. And then they accept it. You just have to be compelling, and keep it ticking all the time.

P. I’ve never heard it articulated as all the characters become the viewer. I might steal that if you don’t mind for a lecture or something.

The victims and their families, I’m curious about how you wove them into the story.

AN. We just tried at a certain point to see what happens if we put them in. For example, when the journalists and their investigation are being dismissed as fake, and you feel their sense of responsibility, and their feeling is ‘’we will fail. How can we prove them wrong?’’ And that just felt like the right moment to come in with Tedy. The way she is exposing herself. We just tried to see what the balance was. We had even stronger scenes with them, but they didn’t fit. They became too personal in a film that has to keep a balance between personal and objective. Once you get too personal you have no chance to get out of there and get back into the investigation of the journalists. It was a lot about instinct, and trial and error. Which parts really resemble an intention and form?

P. Do you feel you can kill your darlings easily?

AN. Oh yeah. I think since my early films I quickly became aware how much it helps a film when you kill your darlings. Because they can cause spikes in a film, that kill the rest of it. That doesn’t mean that I do not fight for them until the last moment, or re-edit them. Sometimes I have 50 versions of a scene, just from trying to rescue it.

P. It’s hard to kill them. But when you realize the balance gets totally disrupted…

AN. It’s about balance, exactly.

P. You lose the point of the film if that particular moment takes all the attention.

AN. Yeah or if a scene already contains all the intention of the whole film. If you’re trying to build a whole narrative and you want the intention to be something that the viewer feels they formulated…. If there’s was one scene that spells it all out, you kill the whole film. You can go home.

It takes a certain kind of person to document political corruption, drug addicts in practice, personal and public conflicts. I have to agree with Alexander that, watching his films I was asking myself “would I do this? Would I not do that?” It’s nice to imagine that I would be as fearless, but you never know until you’re there.

Collective definitely has that sense sometimes that we’re peering behind a curtain we really weren’t meant to see behind. The hair on my neck stood up more than once.

P. Did you ever feel like you were in a tricky situation, or at risk?

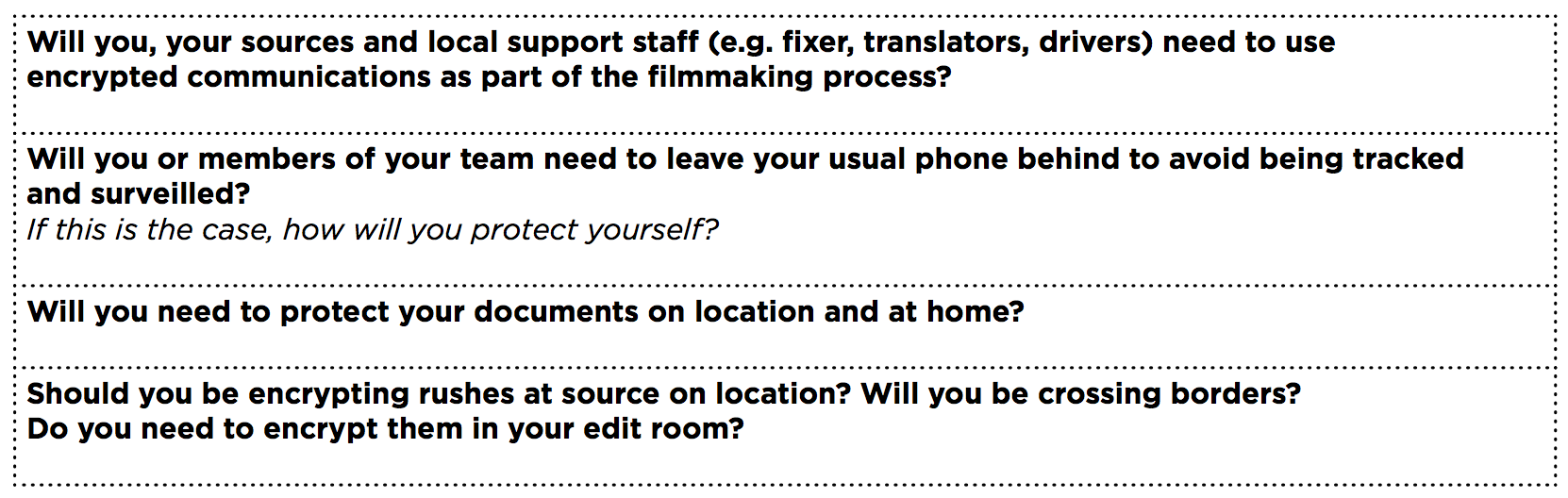

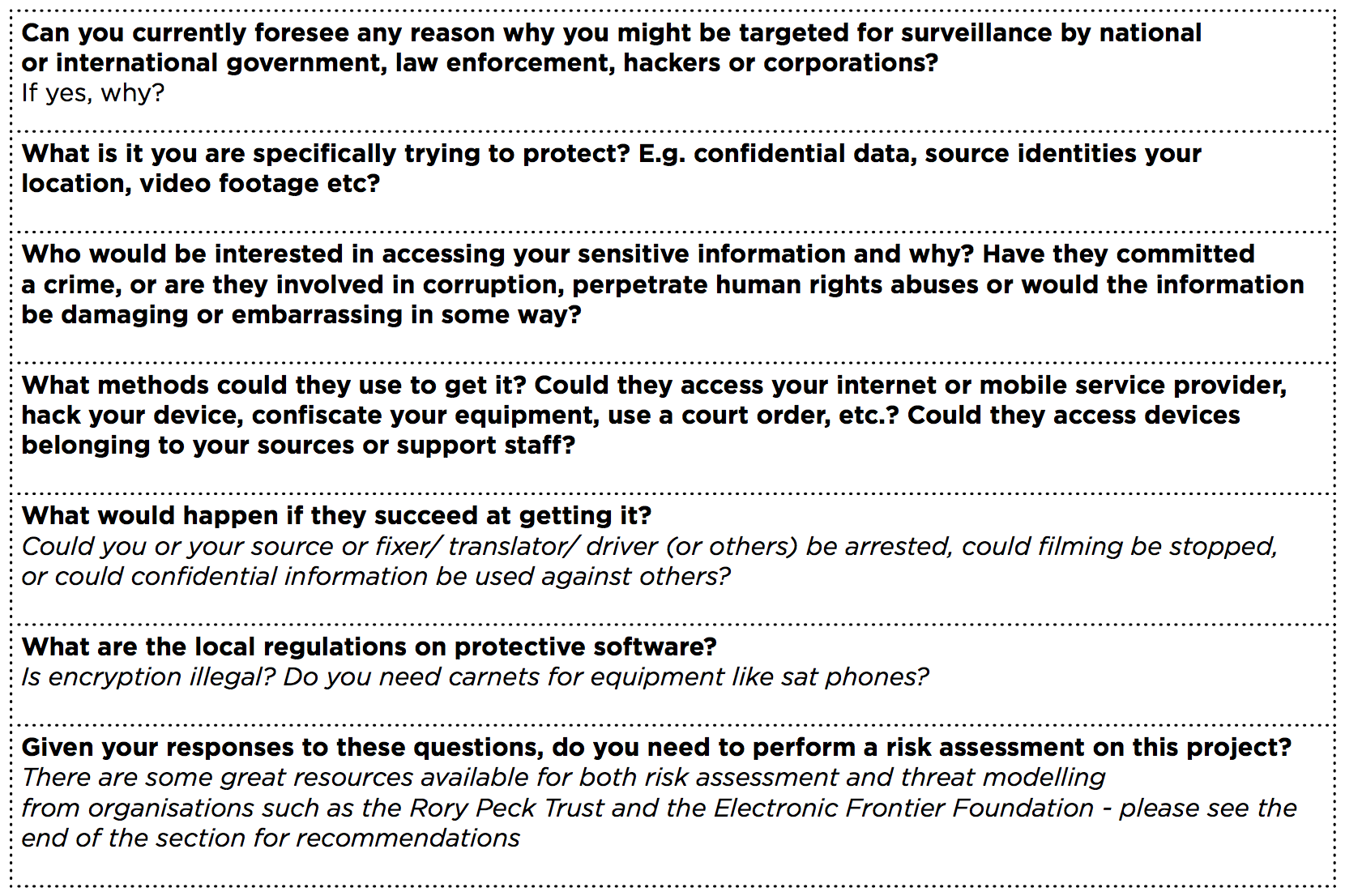

AN. I knew from a source inside the secret service that we were being followed, and my phone was tapped. I didn’t believe it at first, but then they (the source) read to me the date and time that I was talking to people in France and Germany. But I think every state does that. Even the ones that pretend not to. It was clear to me that they (the secret service) were trying to collect information about the journalists’ investigation, through listening to my phone calls. Nevertheless we organized pretty thoroughly to secure our footage. Every evening after shooting we would copy the material onto several sources, hide it, and flew it out of the country. Let’s say we were cautious.

P. Same question about Toto and His Sisters, because those were some pretty dark spaces you were in. Did you ever feel at risk?

AN. There’s a funny story with that one. In the beginning we hired a bodyguard that would look after me and my safety. And they would wait outside, ready for a call from me or my assistants to come in if needed. But nothing ever happened. Maybe one month into the shoot, we came down from the apartment in the middle of the night, and the bodyguard was totally scared. He said “dude, I had such a big rat walk over my shoe! I nearly shit my pants!” He was shaking. So… I said you know, I think I’m safe. You can go home. We cancelled the contract with them and that was the last day that we used them. The people in the ghetto were really good people. And even the young junkies were really smart guys, and people trust me in the ghetto, as long as I’m honest with everybody it’s fine.

P. You could have hired the rats to be your security.

AN. Exactly.

P. I see a deep respect in your films for the observational style. No matter how awful anyone in a scene might be, I never feel like you’re judging them. You let them show themselves. Or hang themselves, in the case of the politicians for example, or Toto’s mom. You treat them as people, and let us reach our own conclusions. Theyre not caricatures. Is observational the way that you always think?

AN. I developed that over time. The most important thing for me is my own attitude towards people. I think that people are basically good. And I believe that everyone is where they are in their lives because of their circumstances, and they had to take decisions. My biggest curiosity is to understand people. Even if they seem bad. Framing is the most important thing in observational style. The way you frame isn’t only the way you see the world or the characters, but the way you capture the authenticity of people, the way you carve out what you think is the definition of someone in a certain moment. That’s also why I prefer to do the filming myself. Until now I wasn’t lucky enough to find a camera person with a similar sensitivity for similar things. That’s why I need to see the story through the lens when it happens, and frame it. Every angle, relative to their eye level, says something about that person. And I believe there’s a sweet spot for everyone along that line which is not judgmental.

If it sounds like the film is this didactic lecture, relax. If that were the case I wouldn’t be bugging Ferrero at home during Easter holiday a couple of weeks after his film screened. In picking icons like the big ole Texan, or the eccentric Italian scientist, he cuts through a ton of narrative grease; because we can identify with the icon, their stories about asshole fathers or loved ones living too far away sit heavy. Whatever Van has to say about the colour of oil, watching him swing an imaginary baseball bat in a broken down baseball diamond in the middle of a wasteland in Odessa Texas tells us everything we need to know about the absurdity of what we’re doing to the planet, or the weight of unfulfilled dreams.

If it sounds like the film is this didactic lecture, relax. If that were the case I wouldn’t be bugging Ferrero at home during Easter holiday a couple of weeks after his film screened. In picking icons like the big ole Texan, or the eccentric Italian scientist, he cuts through a ton of narrative grease; because we can identify with the icon, their stories about asshole fathers or loved ones living too far away sit heavy. Whatever Van has to say about the colour of oil, watching him swing an imaginary baseball bat in a broken down baseball diamond in the middle of a wasteland in Odessa Texas tells us everything we need to know about the absurdity of what we’re doing to the planet, or the weight of unfulfilled dreams.

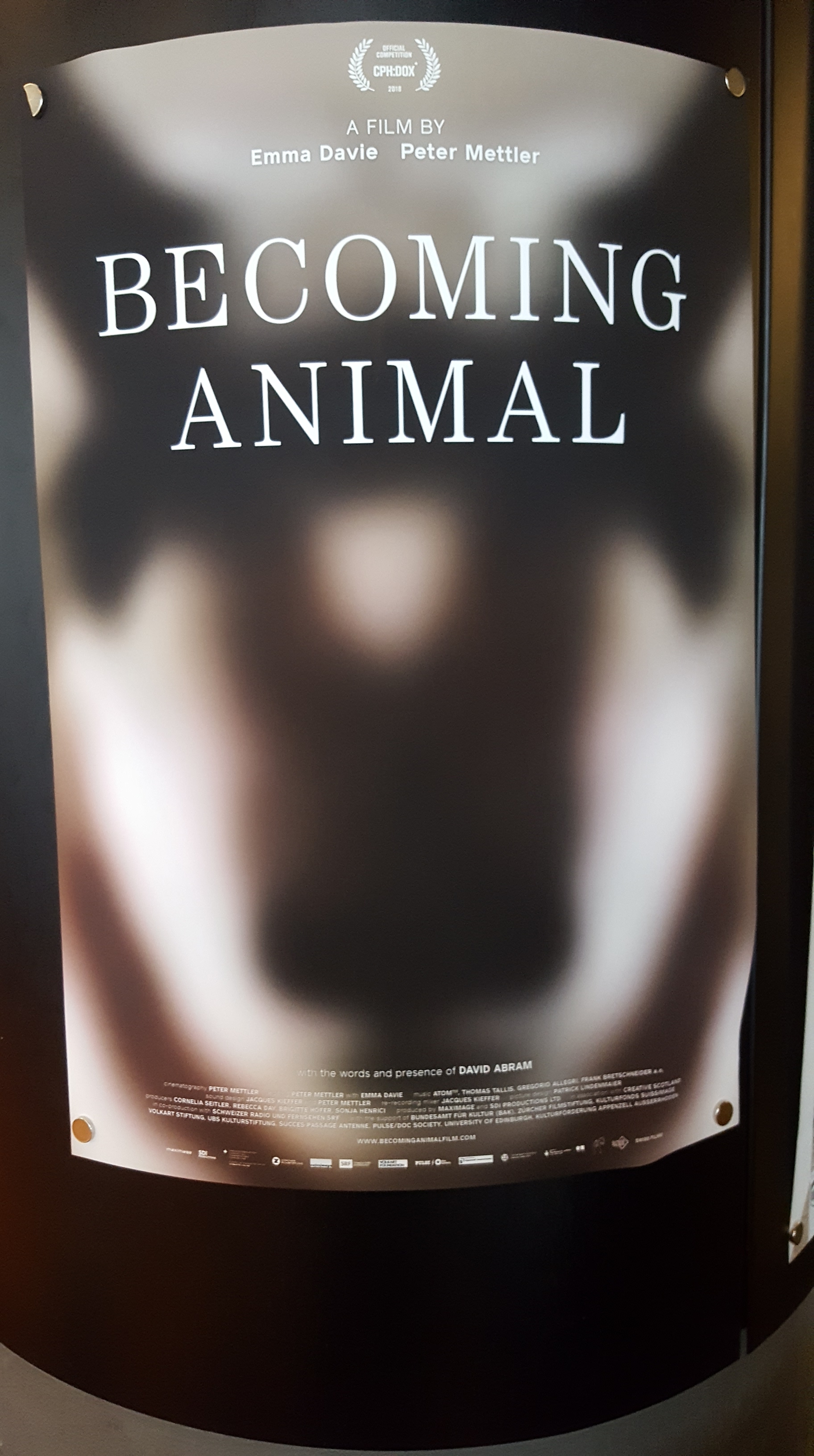

A few years ago I moved to the Swedish countryside. I’ve since re-urbanised, but it was a big thing for me to be surrounded by all that space and silence. Just sitting out in the evening and feeling the cooling air, with the cooing of doves playing on my natural soundtrack. Or lying in the grass with my family staring up at the bats that had nested in the neighbor’s garden. Hell, just being able to ID young wheat stalks, or canola, or the potato stalks in the rows I’d embarrassingly planted crooked made me feel ready to be a survivalist.

A few years ago I moved to the Swedish countryside. I’ve since re-urbanised, but it was a big thing for me to be surrounded by all that space and silence. Just sitting out in the evening and feeling the cooling air, with the cooing of doves playing on my natural soundtrack. Or lying in the grass with my family staring up at the bats that had nested in the neighbor’s garden. Hell, just being able to ID young wheat stalks, or canola, or the potato stalks in the rows I’d embarrassingly planted crooked made me feel ready to be a survivalist.

Today was tough.

Today was tough.

THE MOST UNKNOWN

THE MOST UNKNOWN

I had a tiny hand consulting on this project, but it was my first time seeing it on the big screen. What can I say; it’s a great film! Director Morten Traavik was there for a good Q & A afterwards, and all walked away satisfied.

I had a tiny hand consulting on this project, but it was my first time seeing it on the big screen. What can I say; it’s a great film! Director Morten Traavik was there for a good Q & A afterwards, and all walked away satisfied.

“We had a little over 200 hours of footage to go through, plus a huge amount of broadcast archive. There are a million Syrian stories to tell, and every decision was measured. This story is important because it brings us into the day to day reality of the people left behind. Abandoned.”

“We had a little over 200 hours of footage to go through, plus a huge amount of broadcast archive. There are a million Syrian stories to tell, and every decision was measured. This story is important because it brings us into the day to day reality of the people left behind. Abandoned.”